Azzedine Alaïa, the last of the great independent designers, fully realized the mastery of his craft over the course of his sixty year career. He died on November 18th 2017 at the age of 82, creating right up until the end for his namesake atelier founded in 1979.

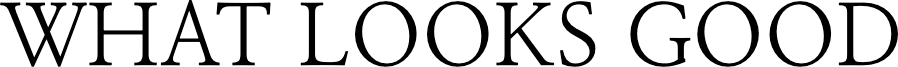

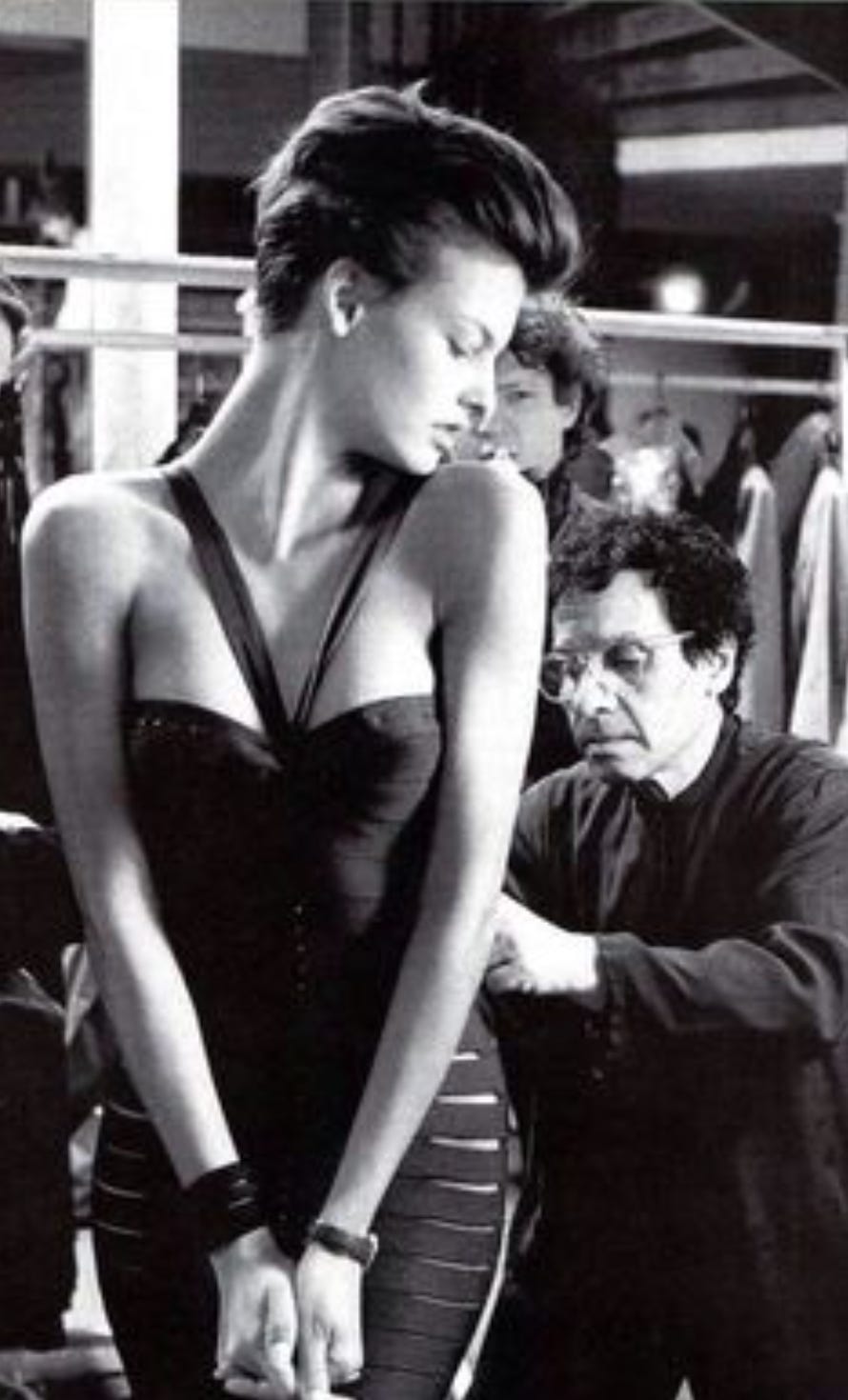

His unique aesthetic and technical expertise brought to fruition clothes that could have come from none other than the master himself. Known for his hyper sexy silhouette of nipped waist and flounced skirts or draped goddess gowns his main objective was to celebrate the female form and make women feel beautiful. His notoriety as a gifted designer was only matched by his reputation as a kind and generous person to those close to him.

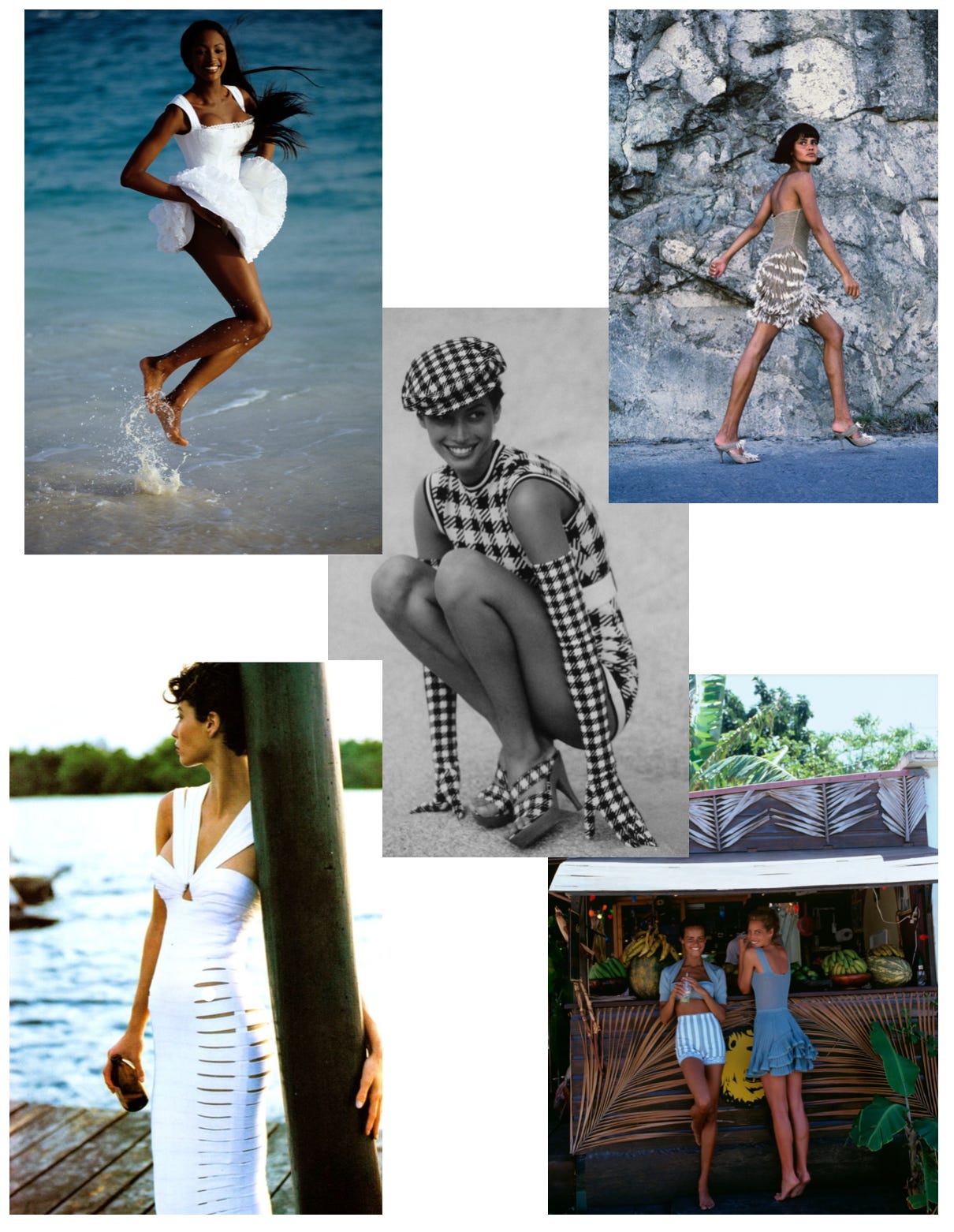

Alaïa was a designer in the purest sense of the word. Each one of his original samples he constructed with his own hands. He draped directly on the model and then worked out the elaborate seaming and self-invented techniques on paper. Though self taught his technical expertise was far beyond that of any working designers today. Only four designers come to mind that had his level of knowledge of construction: Balenciaga, Madame Grés, Vionnet and Charles James. Like them, Mr. Alaïa had a vision that was not influenced by anything other than his own fertile imagination. Designers today are like orchestra conductors, directing teams of tailors, drapers, designers and assistants. Technical expertise is segmented and delegated. I’m not belittling this process, like a conductor it requires skill, vision and a mastery of the materials. I’m pointing it out to emphasize how unusual and gifted Alaïa was.

The system that demands designers and their teams churn out four or more collections a year Alaïa called inhumane and I tend to agree. It takes its toll on the creative process. Designers burn out adhering to the schedule and seldom have enough time to fully explore ideas. As a result designers have become a corporate commodity, unceremoniously disposed of at the end of their contract for fresher blood that will recapture the short attention span of the fashion press. Alaïa presented a show, if he showed at all, only when he felt ready. He never followed a seasonal schedule, instead he worked and let the creative process dictate the schedule. The result of his labor was always an evolution of his unique design vocabulary which transcended seasons and trends. A dress or coat purchased decades ago is just as relevant today as when it was created. His ideas evolved over time, but his look remained constant.

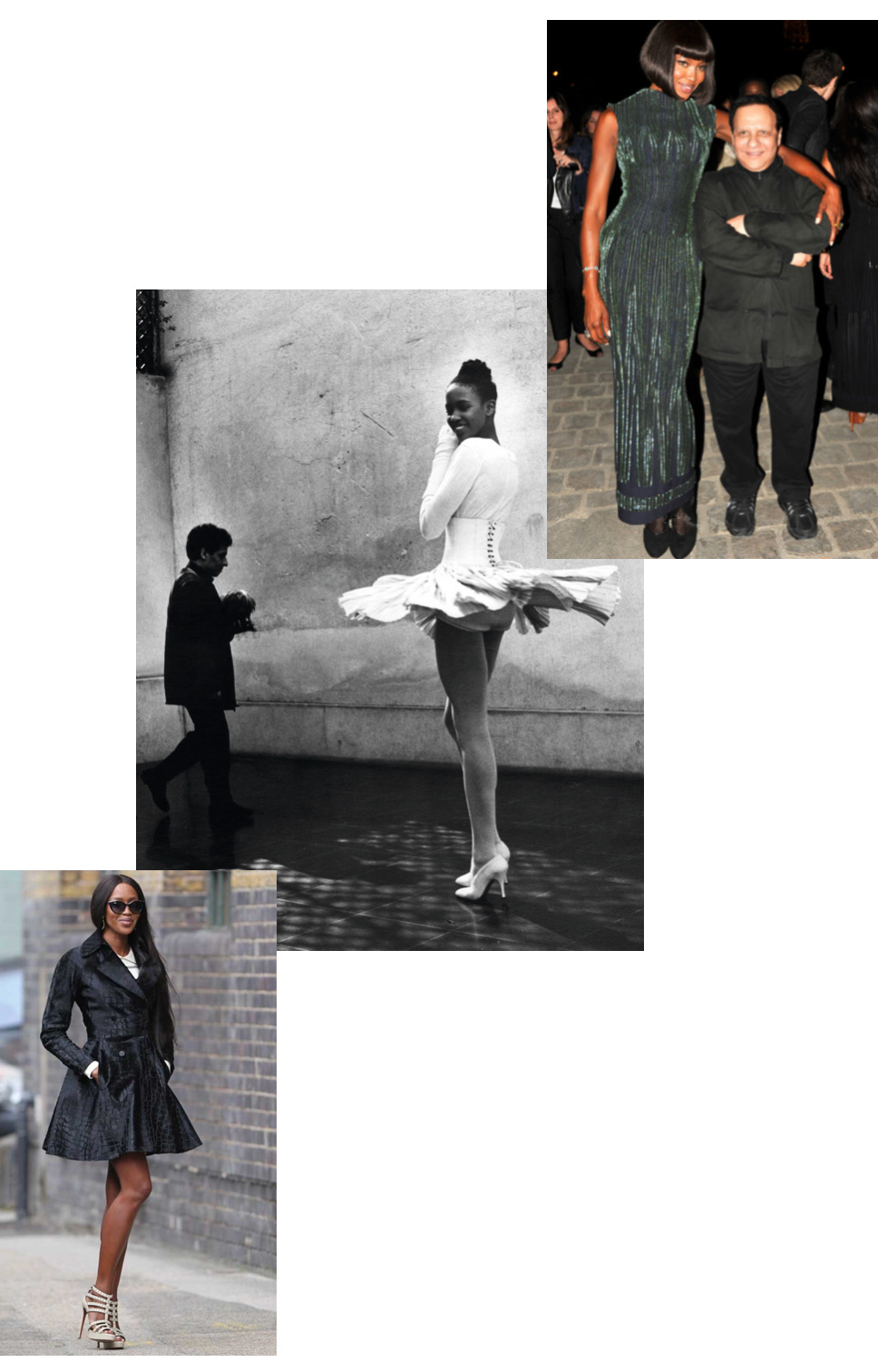

The persona of Azzedine Alaïa was as notorious as his clothes. The tiny Tunisian man was known in equal measures for his big heart (Naomi Campbell calls him Papa) and his iron fist. He ran his company exactly as he saw fit regardless of partnerships with the Prada group, which he eventually bought back, and his sale to Richemont, the current owners of the house.

I had my own fleeting brush with Alaïa years ago. It was the eighties and his notoriety was just beginning to take off. I was on a cheaply funded trip to Paris with friends, brand new to the fashion world. I insisted we seek out his shop while there. We rode the metro to the Marais, then wandered around semi lost before we finally came upon the address only to find the heavy wood door locked. This is long before Google maps and cell phones so it was quite an effort. We finally decided it was a lost cause despite our insistent knocking, and were about to leave when Alaïa, wearing his uniform of black Chinese tunic and pants, approached the door. He was holding his little yorkie in one arm and extending the key to the door with his other hand. He seemed rather annoyed that we were there. The only one among us who spoke enough French asked him if we could come into the shop. He reluctantly agreed and then disappeared into another room. The four of us were left alone in the shop, which was stark in decor and nearly empty save for the handful of treasures hanging from the wooden racks. I was determined not to leave there empty handed. Not nearly as expensive as his clothes later became, I was able to afford a pair of knit leggings, beautifully seamed to make the legs look longer and slimmer. At the bottom were two tiers of knitted lace flounces, very Delight, which was all the rage then. The top was of the same material with his famous U neckline and tight sleeves again with the flounces at the cuff. I was in heaven and felt fabulous every time I wore it.

For a glimpse into the rarified world of this extraordinary talent I urge you to watch the short documentary by the noted fashion stylist Joe McKenna. The documentary successfully captures the warm and insular world Alaïa built, where his domestic and professional life were one in the same. The final scene, which shows him dancing with his enormous Saint Bernard to David Bowie's Let’s Dance, says it all. Here Is the link.

I was surprised to see the extent of the selection of Alaïa on the Real Real. I have always wanted one of the knit dresses. They are beautifully made and timeless. I dare say the dresses from the masters’s tenure will soon be collectors items.

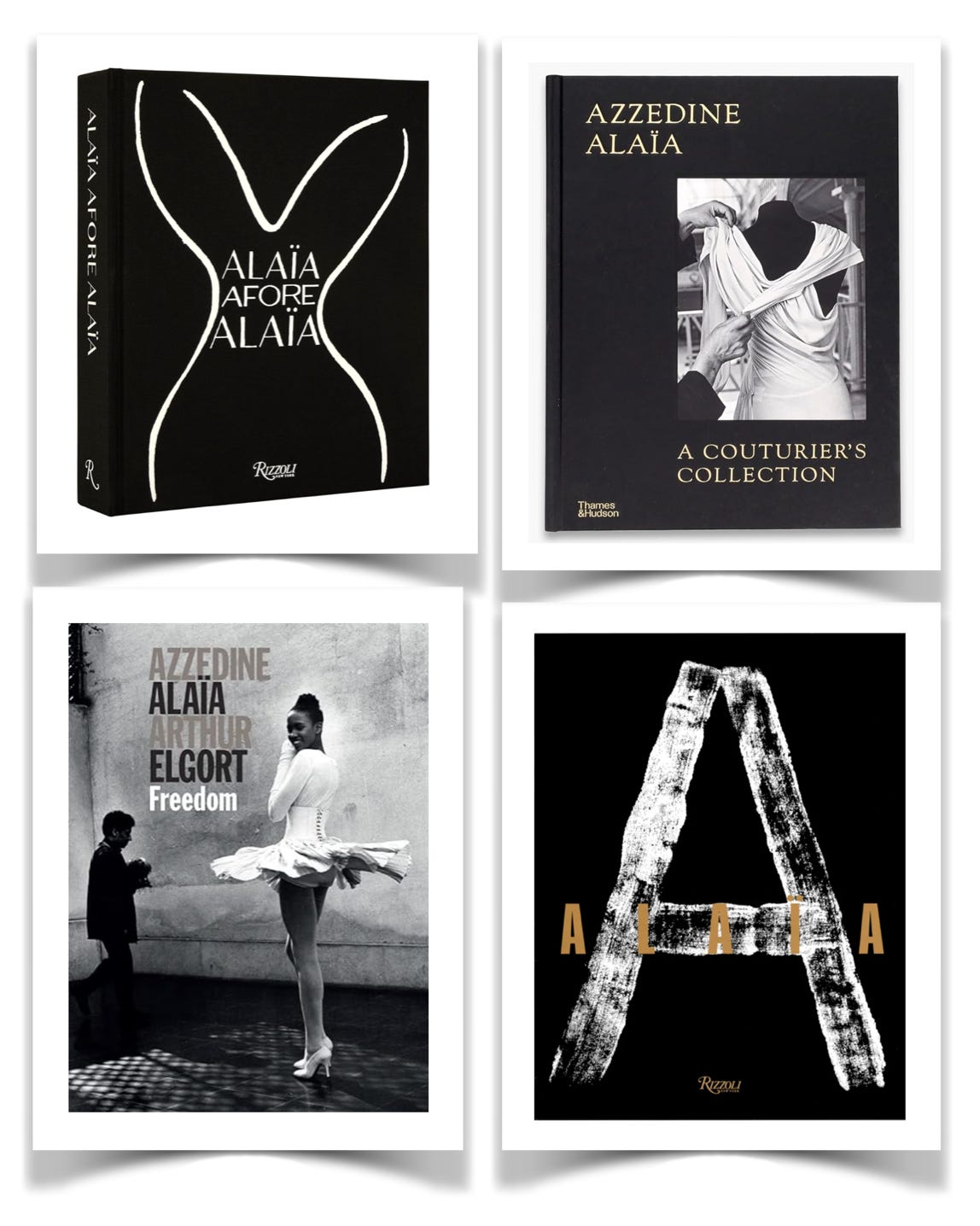

There are a wealth of books on Azzedine Alaïa available. Here is a sampling on Amazon.

A special shout out to Giulia and her excellent Substack The Inside Pocket for suggesting I write about Alaïa in a recent message exchange. This one’s for you Giulia!

He was an amazing designer! Always loved that he didn't conform to the fashion industry and decided to show when he wanted to. What a great story finding his place, meeting him for a moment and then having the place all to yourselves!

Thank you Jolain 🤍🤍🤍 what an incredible piece! I love Azzedine and I knew your words and knowledge on the topic would’ve been impeccable.

I have another book to recommend which is Azzedine Alaïa and Peter Lindbergh by Taschen. It collects the best pictures of a young Naomi in Alaïa!